Acupuncture & TCM Articles

Articles by Mary Elizabeth Wakefield, LAc, Dipl. Ac., MS, MM

Mary Elizabeth Wakefield has 27 years of clinical professional experience as a healing practitioner, and is a licensed acupuncturist, certified by the NCCAOM, a Zen Shiatsu practitioner, massage therapist, a cranio-sacral therapist, Acutonics® practitioner, opera singer, herbalist and Interfaith minister.

She is a graduate of Tri-State College of Acupuncture in New York City, and has studied with such notable acupuncturists as Carolyn Bengston, Kiiko Matsumoto, Dr. Mark Seem, Arya Nielson, Jeffrey Yuen, Dr. Richard Tan, Fabien Maman, Yitian Ni and Donna Carey.

Her knowledge of facial acupuncture and acupressure is based on the work of Jacques Lavier, the "Father of French Acupuncture." She has also studied extensively with her teacher Carolyn Bengston, who is a master of interdermal needling for the face.

For more information about Ms. Wakefield's Constitutional Facial Acupuncture Renewal™ seminars, please visit her website at www.chiakra.com

The Tao of Venus: From Aphrodite to Kuan Yin

By Mary Elizabeth Wakefield, LAc, Dipl. Ac., MS, MM and Michel Angelo, MFA

“The greatest beauty in the world is compassion, love shining free of attachment and grasping.’

– The Tarthang Tulku

In this article, we shall examine two avatars of the divine feminine, the goddess of love, Venus/Aphrodite and Kuan Yin, the bodhisattva of compassion, as they relate to our modern ideas of physical beauty, and the act of renewing oneself by means of facial acupuncture.

Introduction

Far from the stresses of New York City, with its incessant noise, pollution, congestion and pressure, while in temporary residence on a sumptuous 108-acre estate, we find ourselves reclining on a chaise lounge on the shore of Chesapeake Bay, gently lulled into an altered state of consciousness by the murmur of the lapping waves. Instead of blindly obeying the city´s perpetual imperative to “do something, every moment,’ we are beguiled by the unalloyed beauty of nature in this idyllic space of time to “be nothing, every moment … .’

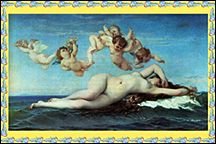

As the hours slipped by, the morning embraced the evening, and this halcyon day seemed immortal … we gazed upon the shimmering blue of sea and sky, and half expected the goddess Venus rise from the whitecaps of Chesapeake Bay – nude, radiant, and unashamed – as in Botticelli´s rendering of her miraculous birth.

Image Right: The Birth of Venus (1863). Image Right: The Birth of Venus (1863).

Artist: Alexandre Canabel (1823-1889).

Since time immemorial, Venus has been recognized as the brightest “star’ in the heavens, except, of course, for our Sun. She was seen as an avatar of the triple goddess – the morning (and evening) star, the maiden who rose every morning, renewed in her youth and virginity, waxing into her full womanhood as the mother, and then, as the crone, gradually waning in her power and strength, only to fade into the darkness of eternal night. She has had many names – Inanna, Ishtar, Astarte, Aphrodite – and has not only represented love and beauty, but also war and fertility; in this manner, Venus likewise embraced the polarities of birth and death.

As the Morning Star, the ancients also styled her the “Bringer of Light’ because, prior to the summer solstice, Venus would rise before the Sun to herald the dawn, moving toward the Pole Star, thereby elevating herself above the lord of the heavens. Observing this behavior, the Greeks thought Venus to represent pride or hubris, because she sought an existence independent of the source, the Sun. Thus the light bringer became equated with the rebel angel, Lucifer, and there was, according to the Bible, war in heaven.

It can be seen from the above that the goddess Venus represents a most complex archetype in human consciousness, and it is perhaps because of this that human beings have a somewhat ambiguous relationship with that most obvious of her attributes, physical beauty.

Beauty Is in the Eye … or Perhaps Not The account of the birth of Venus, or Aphrodite, is one of the most striking of Greek myths, and its central image of the goddess emerging from the sea foam is one that has captured the imagination of Western man for centuries. The sheer vibrant physical perfection of nascent female divinity in this myth has served as a haunting ideal of feminine pulchritude – tantalizing, infinitely desired (and as frequently demonized) for its erotic allure. This birth moment might present to us the beauty of the eye, a ravishing vision forever floating just beyond our reach, inviolate, uncorrupted by time; a quality to which we can only aspire, infinitely elusive and ephemeral.

In contrast, the mythic Venus, far from embodying this notion of beauty as immutable and unapproachable artifact, was the least “stand-offish’ of the Olympian goddesses; she demonstrated a most unambiguous and refreshing concupiscence, and was gifted with both generous and carnal affection and a complete lack of ambivalence about sex. The body, with its manifold imperfections, was sacred to Venus.

Like the king of the gods, Zeus, she was a mediator between the divine realm and humankind, and accessible to human experience; this was reflected in her willingness to mate with mortals, who were also permitted to gaze upon her loveliness without fear of reprisal.

Unlike her divine female relations, Venus/Aphrodite was invariably depicted in the nude; in this, we can perhaps recognize that there is a second component to her beauty, that of revelation. Her nudity may be seen to represent the antithesis of artifice; it is the simple, direct loveliness of the natural world, prodigal, inclusive, all-embracing, constantly changing, and of infinite variety. It is likewise indicative of extreme vulnerability, and ultimately, a manifestation of the inner being, the soul. Her radiance, the rays of the Morning Star, is the ausstrahlung, the outpouring, of her spiritual essence, which Oriental medicine terms the shen. Such luminescence is far removed from a sterile and remote beauty of the eye; it is, rather more, that of the heart, ruled by the Sun, the actual source of Venus´ light. This brings us to a consideration of Kuan Yin, and of the similarities between these two goddesses, who might seem at first to present conflicting notions of feminine beauty.

Beauty Resounds in the Heart

Kuan Yin is traditionally viewed as the embodiment of compassion and loving kindness, a bodhisattva who forswore Nirvana, taking a vow to save all sentient beings. In short, she was a goddess who chose to abide on earth until that moment in time when its every inhabitant had achieved enlightenment. Unlike her Olympian counterparts, she was free of pride or vengefulness, but like Aphrodite, she mediated between Earth and the heavens. Her loving compassion was accessible to everyone without the necessity of dogma or ritual; in the same manner, Aphrodite embraced god and mortal alike.

The name Kuan Shih Yin means “one who regards, looks on and hears the sounds of the world.’ She is receptive and listens to all beings with beauty, love and compassion.

Emergence From the “Patrix’: Embracing Yin and Yang In addition to her female avatar, Kuan Yin had a male component, Avalokitesvara, and was portrayed in this manner as late as the 10th century. With the introduction of tantric Buddhism into China in the 8th century during the T´ang Dynasty, the feminine form gradually assumed greater prominence, and she was invariably depicted as a beautiful bodhisattva in a shimmering white robe. By the 9th century, Kuan Yin´s familiar female likeness could be found in every monastery in China.

The seeming contradiction arising from Kuan Yin´s hermaphroditic nature, as both god and goddess, is explained in the Lotus Sutra: “Kuan Shih Yin may resort to a variety of shapes and travel in the world, to convey beings to salvation.’

Iconography depicts her in a variety of forms, and each aspect reveals a unique facet of her beautiful and merciful presence. In fact, her beauty, grace and compassion present to us an ideal of womanhood for the East, as does Venus/Aphrodite for the West. She was most often shown as a slender woman in flowing white robes; in her left hand, she held a lotus, representing purity. She would either be heavily adorned with jewelry or devoid of ornament, and while the Oriental esthetic refrained from the illustration of feminine nudity, her luminous white robe was almost translucent at times, revealing the outlines of her form in a manner similar to Aphrodite´s golden-hued solar splendor.

East Meets West

Each of these female divinities, while symbolizing beauty in her unique way, has much in common with the other; thus, a synergy of the two may be seen to form a bridge between the ancient and modern world, and perhaps more importantly, between the prevailing attitudes of modern Western society and the philosophy that lies behind Oriental medicine.

How, then, might we describe he tao of Venus as a meeting of these goddesses? How would it manifest itself? Perhaps as a light in the eyes, shining shen, a spirit of compassionate wisdom, of life lived completely in lusty enjoyment, a willingness to renew oneself, to learn, to be creative, receptive, and to listen with openness and impartiality to others, to walk in the path of maturity, to laugh, to express joy and sorrow … to have smile lines around the eyes, to be expressive, juicy, loving, to age gracefully and beautifully.

In the West, the pursuit of beauty has become the quest for eternal youth. This is the legacy of the visual paradigm, the beauty of the eye; physical perfection is to be maintained or achieved at all costs; and, of course, it goes without saying that the slightest wrinkle upon the face, as indicative of character or sign of maturity, is to be erased immediately.

In a society less youth-obsessed, our elders would be honored as the embodiment of wisdom, mentoring the young. Instead, they are discarded, made invisible, because they may have spreading waist lines, and bear the hallmarks of their greater experience and insight upon their faces.

The inheritance of Oriental medicine reminds us that life is a journey; without the presence of shen, reflecting the heart´s compassion, animating the spirit, enlivening the countenance, we are not in harmony with the tao. To paraphrase the poet Madeleine L´ Engle in a poem from her cycle, The Weather of the Heart, it is with “our own souls’ that we are “out of tune.’ With our faces radically frozen by botox, the natural beauty of our smiles distorted by collagen, we graphically portray our fear of aging and surrender to the great void; ironically, we have all-too-willingly subjected ourselves to the embalmer´s art long before the inevitable hour of our mortality. Our unlined faces are mute testaments to an unlived, fearful existence.

The tao of Venus compels us to seek out and inhabit a middle ground between these polar attitudes, to capitalize upon the advances of Western medical science and technology to enhance the quality of individual existence without sacrificing our souls. In embracing the tenets of Oriental medicine, we recognize that our progress upon the path is inherently meaningful, and that it is in the continual unfolding of our spiritual destiny that we are renewed. This is an organic pilgrimage, unique to each person, revered as rich with experience and wisdom, and infused with gratitude for the gift of life.

|