Acupuncture & TCM Articles

Articles by Jake Paul Fratkin, OMD, LAc

Jake Fratkin, OMD, LAc, has been in the practice of Oriental medicine since 1978. Following undergraduate and graduate training at the University of Wisconsin in Chinese language and philosophy and pre-medicine, he pursued a seven-year apprenticeship in Japanese and Korean style acupuncture with Dr. Ineon Moon and a two-year apprenticeship in Chinese herbal medicine with Drs. Zhengan Guo and Pak-Leung Lau in Chicago. He also spent a year in Beijing hospitals interning in advanced herbal medicine, specializing in gastrointestinal and respiratory disorders, and pediatrics.  Dr. Fratkin is the author of several books, including Chinese Herbal Patent Medicines: The Clinical Desk Reference, and is the editor-organizer of Wu and Fischer's Practical Therapeutics of Traditional Chinese Medicine. In 1999, he was named the "Acupuncturist of the Year" by the American Association of Oriental Medicine.

Dr. Fratkin is the author of several books, including Chinese Herbal Patent Medicines: The Clinical Desk Reference, and is the editor-organizer of Wu and Fischer's Practical Therapeutics of Traditional Chinese Medicine. In 1999, he was named the "Acupuncturist of the Year" by the American Association of Oriental Medicine.

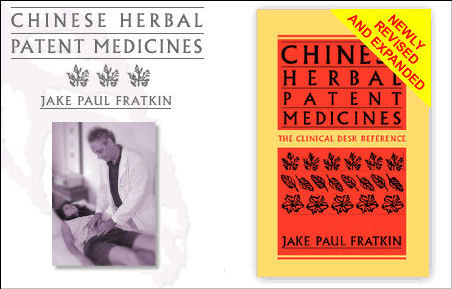

Chinese Herbal Patent Medicines: The Clinical Desk Reference

Hardback book, 1198 pages. This volume covers 1360 products, including 550 GMP level products and all of California FDB analysis on 505 products. Includes information on endagered animals, heavy metals, and pharmaceuticals. The text is organized into 12 groups, with a total of 109 chapters and includes material by Andrew Ellis, Subhuti Dharmananda, and Richard Ko. Over 80 pages of full-color photos (with English and Chinese cross-reference). Fully indexed.

Treating Infants and Small Children With Chinese Herbal Medicine

In China, pediatrics is a TCM specialty, attracting many of the best and the brightest. Some concentrate on pediatric tuina massage for infants; others specialize in herbal medicine. I would like to see more American TCM practitioners train in treatments for infants and children. In fact, such training is available through the Holistic Pediatric Association, which offers a good TCM concentration (available online at www.hpakids.org). Treating children is particularly rewarding. They recover quickly and predictably, especially in contrast to geriatric patients. Children's qi and yang helps their recovery, and the practitioner develops a confidence and optimism in their practice. In the main, formulas used for children are the same as those used for adults. That is to say, children do not require special formulas for common conditions. Determining the correct syndrome differentiation is important. There are certain points one considers in giving herbs to infants and toddlers. Avoid very strong herbs, such as herbs that are too pungent, bitter, warming, cooling or moving. A gentler approach is usually successful. Also, it is recommended that in acute conditions with infants and toddlers, one can discontinue the treatment as soon as improvement is noticed. Momentum should take the child to complete recovery. Dosing considerations: Dosing can be done by age. Whether giving powder, liquid or pills, the Chinese texts make these recommendations:

- Newborns: 1/6 adult dosage

- Babies: 1/3 - 1/2 adult dosage

- Young children (ages 2 to 5): 1/2 - 2/3 adult dosage

- School children: same as adults

Normally, I take a prepared patent medicine (or two) and grind it in an electric coffee grinder. I then return the powder to the original bottle or a plastic zip bag. Or, one can use a Taiwan-style extracted granule powder.

The instructions I give to parents are: Take one-half to one teaspoon of powder. Add a small amount of boiling water, enough to make a dark liquid that is not too watery, thick or pasty. Filter through a metal mesh strainer. From this liquid, use a pediatric syringe and give the following dose:

- Infants: 1-2 ml/cc

- 1 to 2 years: 2-3 ml/cc

- 2 to 3 years: 3-4 ml/cc

- 3 to 5 years: 4-5 ml/cc

- Over 5 years: 6 ml/cc or one teaspoon

Somewhere between the ages of 7 and 12, children are able to swallow pills. I prefer this method or the use of tinctures, and normally give 1/2 to 2/3 the adult dosage. Common clinical illnesses: For many practitioners, treatment of infants, toddlers and children revolves around acute conditions. The most common conditions for infants are colic, fever, cough and vomiting. As children get older, one treats common cold, fever, cough, headache and stomach ache. Parents often seek out alternative practitioners for chronic conditions like eczema, asthma, insomnia, constipation and behavioral problems such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

By the time a child is 6 or 7 years old, standard TCM differentiations may be applied, and we use pulse, tongue, as seen in adults. (Children at this age will have slightly faster pulses.) For diagnosis of younger children, we rely on symptoms and history described by the parents, although tongue and palpation are helpful.

Pathophysiology considerations: In children, the three systems that are most commonly affected are digestion (spleen-stomach), lungs and the immune system.

The digestive systems of infants are immature and delicate. They are easily injured by overeating or by food that is too cold or too rich (spicy, fatty or sugary). Cow's milk would be considered too rich and fatty, and often leads to food stagnation. Food retention caused by overfeeding is responsible for vomiting, colic, diarrhea, malnutrition and anorexia (poor appetite). In these cases, effective formulas include bao he wan. Occasionally, wind-cold can lead to food retention, and an effective formula is huo xiang zheng qi wan. In cases of constipation with fever in infants, saline enemas, purchased in drug stores, are quite effective. Acute constipation in older children can be treated with formulas that contain da huang (Radix rheum). In acute situations of food poisoning or stomach flu in toddlers and young children, again, huo xiang zheng qi wan would be the medicine of choice. Infants and toddlers are susceptible to exogenous pathogenic factors (wind, cold, dryness, heat, summer-heat and damp). Appropriate formulas for wind-cold and wind-heat can be used. The ones I use most frequently are xiao qing liong tang for wind-cold and yin qiao san for wind-heat. For older children, I frequently use the patent medicine gan mao ling. For wind-heat-dryness, showing dry cough, I like to use sang ju yin. If untreated or ignored, pathogenic factors will remain in the body. This can manifest in the lungs and sinus as phlegm, in which case formulas such as qing qi hua tan wan are effective. If the pathogens settle in the lymph or tonsils, one can combine xiao chai hu tang with pu ji xiao du yin. As far as boosting the immune system, I rely on either yu ping feng wan or astragalus vials (huang qi). This is especially effective during the pollen allergy season. When to treat, when to refer: Treating children takes study, enthusiasm and some degree of confidence. Many parents are quick to jump to Western medicine, but the experienced practitioner knows when to treat and when to refer. Referring, in my opinion, means that the child requires hospitalization. I say this because conventional medicines for non-hospitalization illness in infants and children can be quite damaging. Many pediatricians rely on antibiotics and steroids for treating a majority of pediatric conditions, when herbal medicine or acupuncture offers effective and much safer alternatives. The TCM pediatrician should see themselves as an alternative to Western pediatricians for the outpatient level of common problems. Hospitalization, when necessary, however, draws on the true power and knowledge of Western medicine in order to save life or limb. As an example, let us look at an uncommon presentation. True meningitis (a bacterial or viral inflammation of the brain or spinal cord) must be treated in the hospital in order to save a life. Isolated convulsion with high fever may not. If the TCM practitioner is successful in lowering the fever, a non-meningitis convulsion should not repeat itself. Arching of the spine or continual or repeated convulsions, are dangerous signs, and the experienced practitioner should know the child needs hospitalization. When we embrace the practice of pediatrics, training should be at the seriousness of this level, realizing that severe illness can attack a young child. We must know when and how to refer, whether to the hospital's emergency room or to a conventional pediatrician. Julian Scott, a great pioneer and advocate for TCM pediatrics in the West, said in a lecture, "Only go into pediatrics if you genuinely love children." Otherwise, if they are irritable or uncomfortable, they will drive you crazy. This love for children makes the clinic light and cheerful. They always make me laugh or smile, and in turn, that makes them relax. Some pediatricians in Oriental medicine talk about creating a kid-friendly clinic with toys, pictures and gifts, but I think what is truly necessary is a heartfelt connection with the child. When they know that you like them, whether a 3-year-old or a 16-year-old, they enjoy coming in and they trust the medicine. This does not mean that there are no boundaries or that the clinic is a playroom. It is not. It is important for the child to be focused on why they are in the clinic. I always look the child in the eye and say this: "The medicine will not taste very good. Swallow it quickly, and then have something to take the taste out, like water or juice. But if you take the medicine, you will get better quickly." I say this with belief and kindness and because of that, children take their medicine. More importantly, they come to rely on Chinese medicine when they get sick and ask for it, in spite of the taste. And they grow up knowing something very deeply: that Chinese medicine works.

Recommended Reading: For an in-depth overview of TCM pediatrics, see my outline, Overview of TCM Pediatric Pathophysiology and Diagnosis, in the following texts:

- Cao Jiming, Su Cinming, Cao Junqi. Essentials of Traditional Chinese Pediatrics Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1990. Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1990.

- Luan Changye. Infantile Tuina Therapy Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1989. Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1989.

- Wu Yan, Warren Fischer. Practical Therapeutics of Chinese Medicine , edited by Jake Fratkin. New York: Paradigm Publications, 1997. , edited by Jake Fratkin. New York: Paradigm Publications, 1997.

|